NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

On the eastern edge of Missouri, leaders of the Alive and Well network had generated a robust media campaign to help people understand the impact of trauma and toxic stress on health and well-being. There was a monthly column in an African-American newspaper, spots about toxic stress and resilience on urban radio stations and weekly public service features on the NBC affiliate, with physicians, clergy and teachers advocating ways to “be alive and well.”

Two hundred and fifty miles to the west, a similar cross-sector coalition, Resilient KC, was sponsoring workshops, hosting a learning collaborative and recruiting community “ambassadors” who could bring the science of ACEs and resilience to clients, colleagues and policy-makers in business, the armed services, education, justice and health care.

On both sides of the state, those networks saw their grant funding trickling to an end. So they decided to join forces, share strategies and form a not-for-profit organization that could spread the impact of their work across Missouri and the region.

Resilient KC—a partnership between a pre-existing network, Trauma Matters Kansas City (TMKC), and the Greater Kansas City Chamber of Commerce—was one of 14 locales to receive a two-year Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) grant. The work drew interest from the local arts community, the Kansas City Royals and the police; Captain Darren Ivey became a tireless champion, consulting with other police departments and designing trainings on vicarious trauma.

But as the MARC grant drew to a close in 2017, Resilient KC leaders thought about how, “if we really want to sustain the movement and think about where we are going in Kansas City, we need to be a not-for-profit,” says Marsha Morgan, who helped launch TMKC while working as chief operating officer of Truman Medical Center’s department of behavioral health.

Meanwhile, leaders of Alive and Well St. Louis, under the auspices of the regional health commission, knew that their mission—increasingly focused on racial equity—had grown beyond the bounds of a health-focused organization.

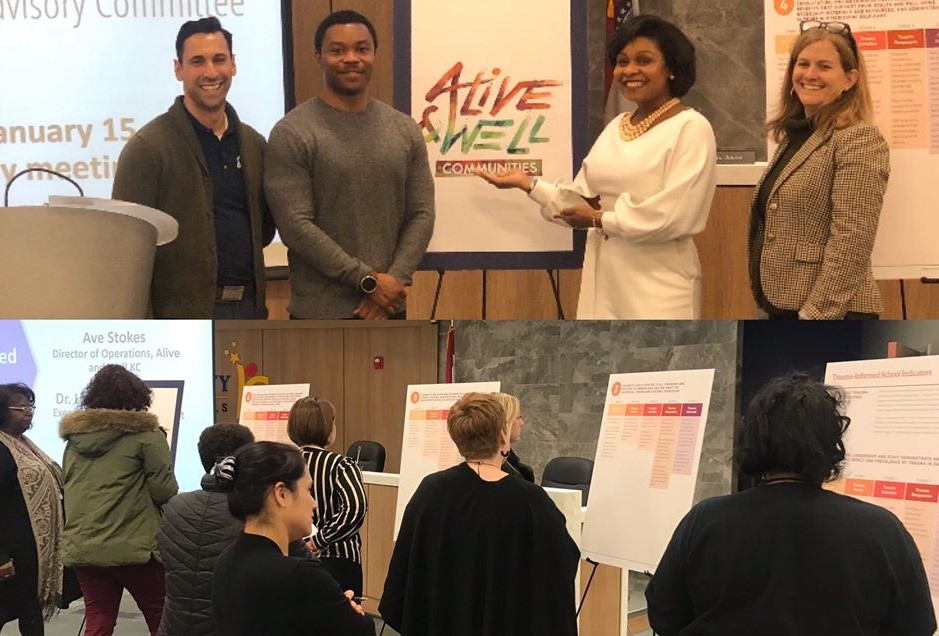

“We kept turning to our partners in Kansas City to ask, ‘How do we do this?’ We shared information and expertise. We were both trying to solve the same problems,” says Jennifer Brinkmann, now president of Alive and Well Communities, launched as a 501c3 in early 2018.

Alive and Well built a structure that reflects the network’s aim to make change both at the “hyper-local” and institutional levels. To accomplish that, the network recruited 500 “ambassadors,” community volunteers who attend a two-hour trauma awareness training and elect a steering committee— one in St. Louis, and one in Kansas City—to set priorities and drive the work locally.

In St. Louis, Alive and Well also hires neighborhood residents—individuals who are interviewed, trained and paid an hourly rate to deliver workshops on trauma, self-care and community care.

A 13-member volunteer board of directors—including the two co-chairs of each steering committee—holds financial responsibility for Alive and Well. They include representatives from academia, health care, human services and the faith-based community.

Alive and Well also joined the national Building Community Resilience Collaborative—a means of having an impact on federal legislation, such as a recent appropriations bill that included guidance to address health disparities and the trauma of racism.

For Ave Stokes, director of Kansas City programming for Alive and Well, listening and flexibility are key to engaging a racially and economically diverse range of residents. That may mean changing the place or time of events—locating them in different neighborhoods, holding them in the afternoon or evening to accommodate people with varied work schedules. “Let people in communities tell you what works for them,” he says.

Stokes cites the success of the “impact series,” discussions in Kansas City public libraries focusing on the links between trauma and child abuse, domestic violence or black maternal health; the sessions are meant to inform and empower listeners to take action. Between 80 and 250 people have attended each one.

Leaders on both sides of the state note the added value of cross-sector efforts: when schools in Johnson County brought together representatives from public health, education, law enforcement and mental health to focus on the needs of high-risk students, or when the Kansas City police department added five social workers to its staff, or when Alive and Well hosted a 2019 convening of 200 people to hammer out a common vision and language for building trauma-informed communities across the region.

One ongoing challenge, says Brinkmann, is keeping up with the demand for training and assistance that goes beyond a baseline understanding of ACEs and trauma. Alive and Well provides that support—in fact, such paid consulting work helps fund the network’s community-based efforts—but the work is time-intensive and can be out of reach for the cash-strapped organizations that may need it most.

“There are some communities in rural Missouri that are saying, ‘We need Alive and Well here,’ but we don’t have the bandwidth to provide support at that level,” she says. “I think for the work to have the impact we all want it to have, we’re going to have to get into policy change work. Teaching people about ACEs is just scratching the surface.”

Morgan agrees. “We need to spend time in an organization to help them put in the structure, to really help them understand and provide intervention at a different level. We need to move from awareness to responsiveness.”

She, Brinkmann and Stokes would like to see more involvement from the corporate and business sector, from justice and probation systems, and from primary care health practitioners. Still, they are heartened by Alive and Well’s achievements: 251 trainings, reaching more than 5,000 participants, in 2019; the publication of the Missouri Model for Trauma-Informed Schools; surveys indicating that 99% of attendees in St. Louis community empowerment workshops said the trainings would change their behavior.

“For me, it’s extremely rewarding to be in community with our ambassadors—people who care so deeply about making their communities better,” says Brinkmann. “It’s in those moments that I find hope that we can get there, collectively.”