NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

Leaders of Buncombe County’s ACE Collaborative learned quickly that bringing agency professionals and community members together in the name of resilience-building was harder than it sounded.

Sometimes the leaders’ invitations to trainings or guest speakers drew just a trickle of response. Other times, the room crackled with tension—on one side, representatives of Buncombe County Health and Human Services (the backbone and fiscal agent for the Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities project); on the other, community members wary of a government agency and unsure about why they’d been asked to the table.

“It was not comfortable at first,” says Jan Shepard, the county’s health division director. “We had to sit back and say, ‘We’ve got to let the community tell us what their needs are and in what ways we can support that.’ That was harder than any of us thought. It was an enormous growth exercise for everyone.”

It helped to bring facilitators trained in conflict management, who could help participants reframe a volatile discussion and stay focused while acknowledging strong feelings. And it helped to take time, maintain patience and slowly build trust.

“How do we make sure that decision-makers and funders have a really good understanding of the time it takes and the difficulties and skills involved in doing that well?” Shepard asks.

Supporting resilience-building with tipping grants

As ACE Collaborative leaders ponder that question—especially as they look toward sustainability beyond year two of the MARC project—they are also honoring local resilience-building efforts with “tipping grants,” infusions of up to $5000 for a range of initiatives in education, health, cultural preservation and community-building.

As ACE Collaborative leaders ponder that question—especially as they look toward sustainability beyond year two of the MARC project—they are also honoring local resilience-building efforts with “tipping grants,” infusions of up to $5000 for a range of initiatives in education, health, cultural preservation and community-building.

In the first round, the Collaborative reviewed 70 applications and awarded 14 grants, which included training and development assistance along with funds. One woman, concerned about high school students who did not see college as a viable option, received a tipping grant to take 20 students and their parents on a tour of regional campuses. The results of that trip far exceeded expectations—and even crossed generations: One of the parents is now determined to complete her own college education and is receiving help from the tipping grant’s leader to find resources.

Another tipping grant went to My Sistah Taught Me That – a female cohort of the already established young men's youth development program called My Daddy Taught Me That. A community garden program received a grant to promote nutritious eating along with social justice and an ethic of volunteerism.

“The purpose was to give lift to what is already going on and for it to be embedded in communities so it has a public will and a public voice,” Shepard says. “We’re seeing people who are doing similar work starting to collaborate more.”

Those grants have also shifted the balance of power and trust, she says. “Through our call for action and tipping grant applications, we have really engaged our communities that experience the most adversity. We’re starting to see people let their guard down, where maybe we were kept at arm’s length before.”

Planning leads to resources

For the Collaborative itself, year one of the MARC grant brought a strategic planning process that included the election of co-chairs (one child psychiatrist and one parent of a child with special health needs), the development of committees and a leadership team, and the start of plans for an anchor institution to fund a coordinator so the work can continue.

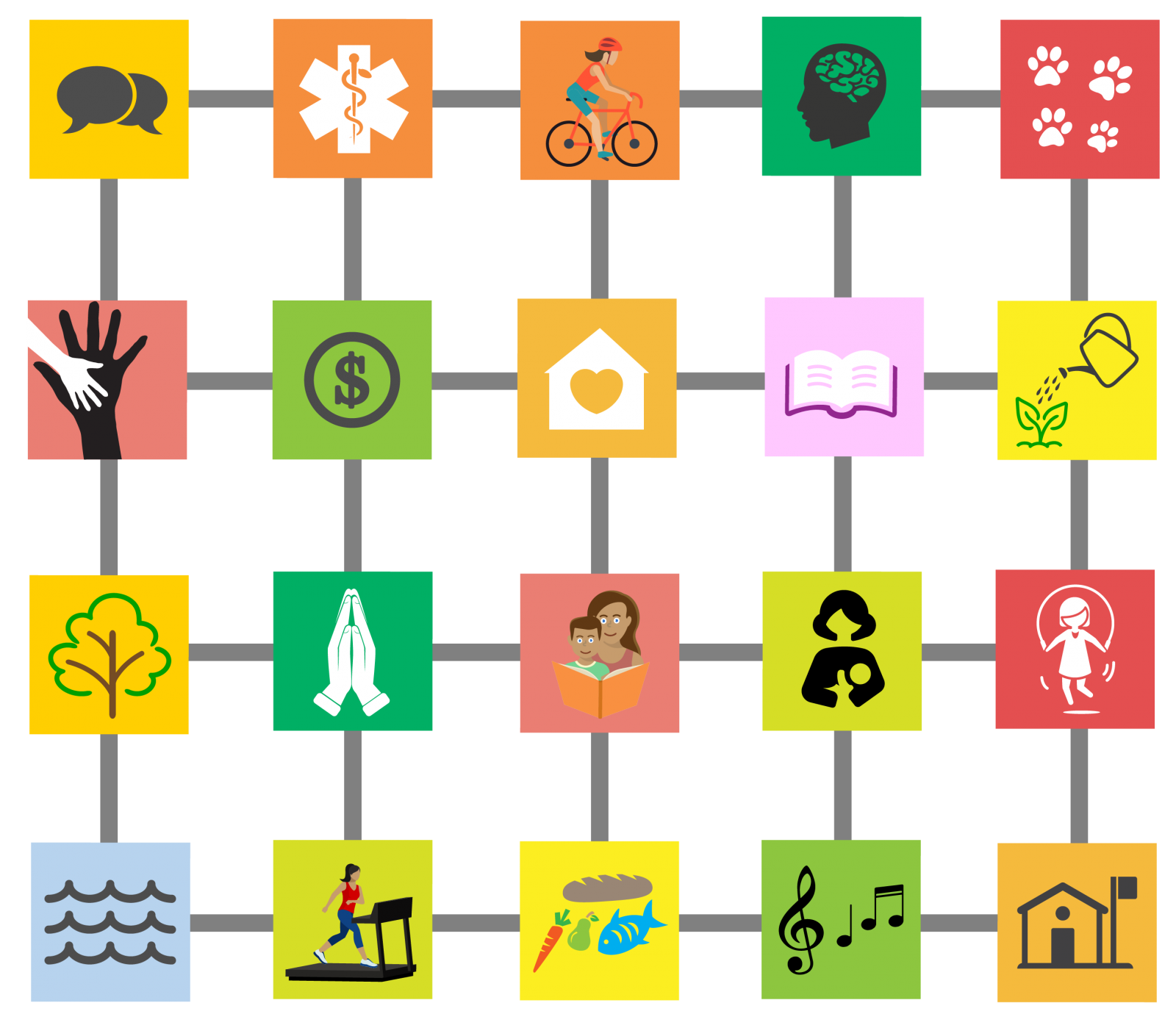

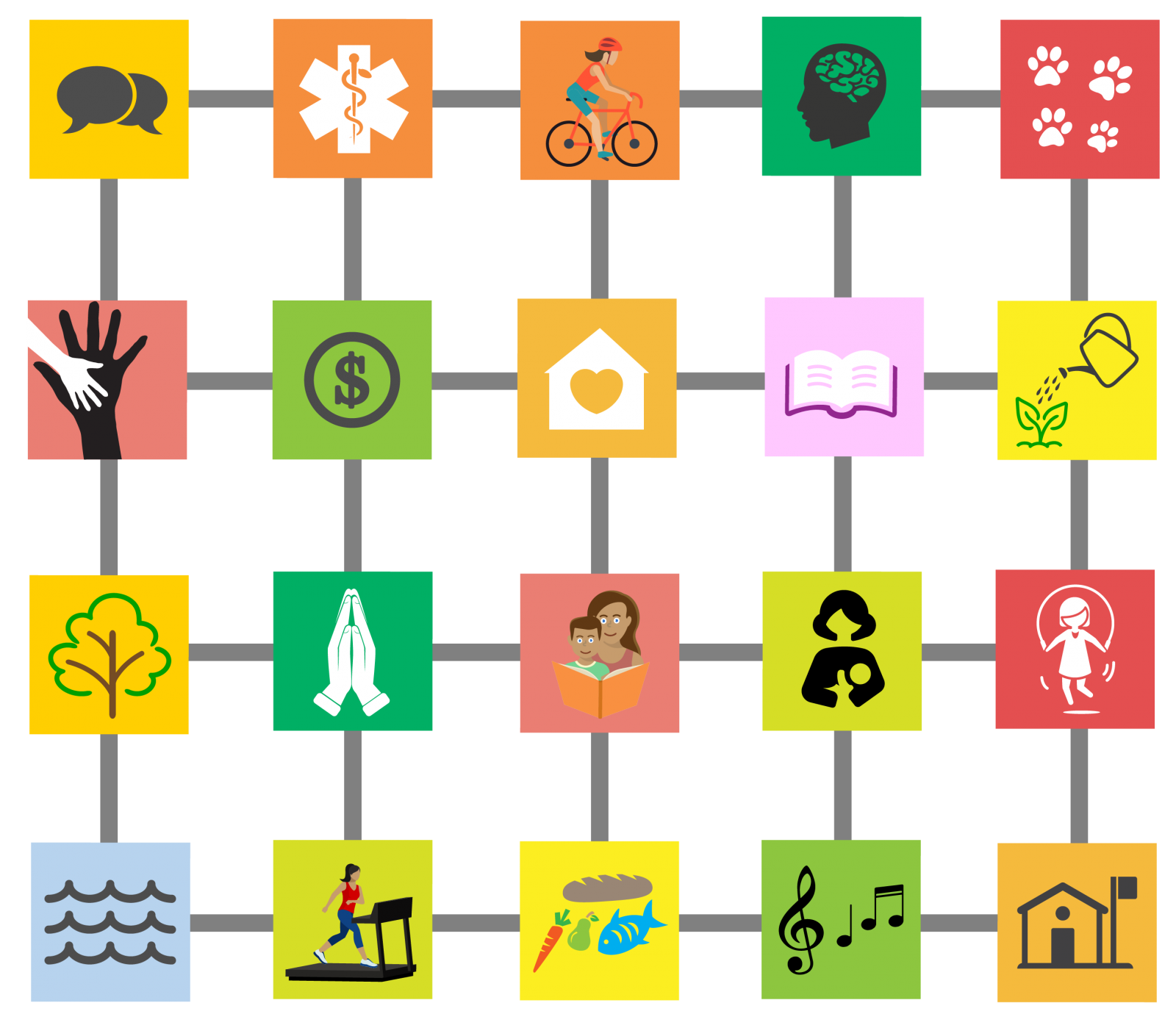

Another focus of year one was to develop consistent, potent messaging about ACEs and resilience. For that, the ACE Collaborative worked with the FrameWorks Institute of Washington, D.C., which helps non-profit agencies frame public discourse. They devised visual metaphors with punch: a “resiliency scale” that can tip either way based on positive or negative experiences in life, and a “resource grid” that demonstrates how social, health and educational supports—places of worship, parks, mentorship programs and the like—help whole communities to thrive.

“We use those two metaphors and visuals in almost every communication we do,” says Shepard, and the images are beginning to stick: she often hears of community meetings in which participants used the resiliency scale or made reference to the resource grid. Engaging with resilience-building

Engaging with resilience-building

She’d like to see the region’s broader business community, and its faith-based organizations, become more engaged with the work of resilience-building. ACE Collaborative leaders also want to find ways to collect and share powerful stories of working through adversity—perhaps a traveling exhibit of photographs and narratives. They’d like to create a way to assess the value of the tipping grants without raising onerous barriers for community members who wish to participate.

“Because we are a local government agency, we had some challenges providing these small grants in the way we wanted to, not looking to box applicants into a plot of deliverables,” Shepard explains. “We want to really understand how the tipping grant process can continue to build resiliency, and how we can do it better and give more lift to our community.”

Teaching skills to manage adversity

Shepard remembers one of the many times ACE Collaborative leaders tried out the FrameWorks metaphors. On this occasion, the audience consisted of children aged 9-12. Organizers dumped out bags of sticky notes and pens and explained the process: Write down all the good things in your life, and all the things that make life harder, then stack the sticky notes on either side of the scale.

She watched as the children scribbled away: I have a big brother. My mom and dad fight a lot. I have a bicycle that’s mine. I don’t have anywhere to go after school.

“You could see in their eyes and their faces a little light bulb go off: Wow, if I take that [negative] one off, my scale goes up this way! If this is something kids can understand, and we’re helping equip them with skills to manage all the adversity in their lives, that is important work for the future of these children and our community.”

This article is part of a community update series following the ATR networks participating in the MARC 1.0 Initiative. Read the other updates from Buncombe County, NC: