NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

The week of the fall equinox was Mino-Bimaadiziwin Wellness Week at the Saginaw Chippewa Academy (SCA) in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan, a pre-K through 5th grade school of about 130 students.

“Mino-Bimaadiziwin” is an Anishinabe phrase meaning “to live the good life.” At the school, it started with “Mindfulness Monday”—students were encouraged to wear their favorite “thinking cap”—then segued to “Take care of our bodies Tuesday,” a “Love Your Community Wednesday" that included talking circles, and a “Take Care of Our Spirits Thursday” with t-shirt decorating and a meal featuring wild rice that’s central to Ojibwe culture.

Throughout, teachers emphasized Tribal traditions and healing practices: the medicine wheel; a sema (tobacco) ceremony; attention to the passage of seasons and the Indigenous calendar.

“It was like Spirit Week, but focused on building resilience and connection,” says Kehli Henry, community project manager for the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe (SCIT) of Michigan. Henry also coordinates Project AWARE, a multi-sector collaborative funded by a $9 million federal grant, which aims to boost mental health, access to community services and protective factors for students at SCA and in two public school districts.

The path to Project AWARE began five years ago, when SCIT Education Director Melissa Isaac became SCA’s interim principal. She noticed overwhelmed teachers and struggling students. Then, a series of tragic community events left 60% of one classroom without their fathers and sent a wave of grief throughout SCA. In a close-knit community, somebody’s father was also another student’s uncle or cousin. Isaac realized she had to seek a trusted, behavioral health professional for help.

Teachers at SCA (The Saginaw Chippewa Academy) began to talk with Sarah Winchell-Gurski, the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe’s school-based consulting clinician, about what they were seeing in their classrooms.

Students had “lots of problems with being able to pay attention, acting-out behaviors. Connection, emotional regulation…way more than what we would see in an average classroom,” says Winchell-Gurski. She became an ACE master trainer in 2016; she recognized the roots of what teachers were describing.

So she began to ask questions. “We did an off-the-cuff preliminary ACEs screen,” talking with school counselors, administrators, teachers and the tutors and advocates who work in the Tribe’s K-12 education program: “What is this population dealing with? What was going on with their families?” They asked not only about the ten ACEs cited in the landmark 1998 study, but about traumas unique to a Tribal population: the ancestral, trickle-down losses of language, tradition, land and history.

Winchell-Gurski recalls that not everyone was eager to learn the answers. “There was fear: if we really acknowledge how much trauma our kids are dealing with, then what?…What we did from there was to just say, ‘Okay, what can we do with this information rather than to continue to allow this to happen?’ That was the beginning of our trauma-informed journey.”

Tribal education leaders began looking for funding opportunities; in 2019, they received a five-year Project AWARE grant from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), a partnership between the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe and the Mt. Pleasant and Shepherd public school districts.

The grant paid for additional staff—ten new counselors across the three districts—along with annual trauma-informed training for school personnel; the first round, in August 2019, included over 600 staff. Project AWARE also aims to go beyond the schools themselves, building bridges to non-profit agencies, private providers and other community supports, Henry says.

The grant paid for additional staff—ten new counselors across the three districts—along with annual trauma-informed training for school personnel; the first round, in August 2019, included over 600 staff. Project AWARE also aims to go beyond the schools themselves, building bridges to non-profit agencies, private providers and other community supports, Henry says.

For instance, the schools now partner with HopeWell Ranch, which offers equine therapy, and are reaching out to other local organizations and providers to learn more about their services and connect them with the schools. For example, Listening Ear provides a 24-hour crisis line as well as a runaway and homeless youth program and residential services for those in need. Those connections and collaborations matter, says Henry, because schools’ resources are limited; it takes an entire community to support healthy students and families.

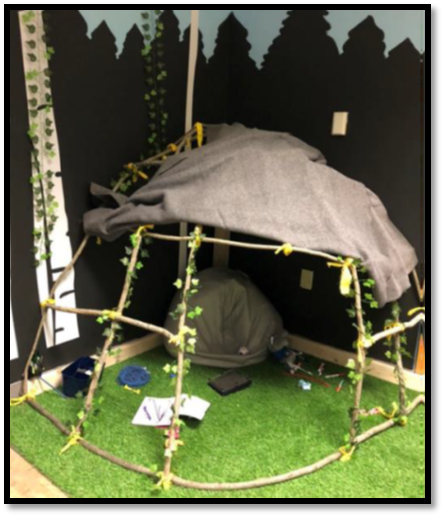

In addition, the grant provided funds for teachers to create “calming corners” in their classrooms—areas in the room filled with sensory objects, weighted blankets, brain-teaser puzzles and other items to help children self-regulate without having to leave the room. Funds from the Tribal government’s 2% Grant program paid for therapy dogs for the schools.

In addition, the grant provided funds for teachers to create “calming corners” in their classrooms—areas in the room filled with sensory objects, weighted blankets, brain-teaser puzzles and other items to help children self-regulate without having to leave the room. Funds from the Tribal government’s 2% Grant program paid for therapy dogs for the schools.

Project AWARE also aims to raise awareness and attention to staff wellness—especially at a time when some teachers are working double shifts in a hybrid school model, teaching both in-person and online classes each day.

The biggest outcome so far, according to Henry and Winchell-Gurski, is a change in perspective on the part of teachers, administrators, counselors and other adults who interact with children.

“Behavior is a form of communication,” Henry says. “It’s [a matter of] shifting that mindset from a punishment model to a trauma-informed model—understanding why the student is exhibiting that behavior.”

Winchell-Gurski, who has also provided ACEs-and-resilience training to Tribal staff, health care workers, day care providers and volunteers, recalls a kindergarten teacher who felt so despondent about one child’s persistent tantrums that she would cry at the end of each work day. Winchell-Gurski visited the classroom, observed the child and helped the teacher figure out that the girl could manage transitions more comfortably if she was given a five-minute heads-up, was able to lean physically on the teacher and had opportunities to hang upside-down in her chair, a posture that can foster relaxation for some children.

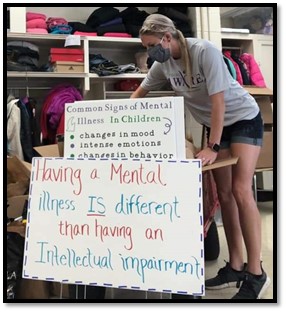

While COVID-19 put a halt to in-person planning meetings and large-scale trainings, Project AWARE has continued to provide resources during the pandemic: a Zoom session for families on “parenting during COVID,” developed by a Mt. Pleasant counselor, and a collaborative school-supply distribution in the Shepherd district, with backpacks that included information on mental health and service provider contacts along with pencils and notebooks.

While COVID-19 put a halt to in-person planning meetings and large-scale trainings, Project AWARE has continued to provide resources during the pandemic: a Zoom session for families on “parenting during COVID,” developed by a Mt. Pleasant counselor, and a collaborative school-supply distribution in the Shepherd district, with backpacks that included information on mental health and service provider contacts along with pencils and notebooks.

Project AWARE will collect data to gauge its effectiveness—the statistics SAMHSA wants, such as the number of students seen by the schools’ new counselors, as well as measures of student attendance, academic achievement and changes in disciplinary actions.

“The level of collaboration has definitely increased,” says Henry. “But it takes a long time to shift mindsets and school cultures.”

Meantime, the goal is to keep building connections—between teachers and families, between schools and their communities—with the aim of a fully trauma-informed community, says Winchell-Gurski. “Every single person you can share the information with is going to create that ripple effect. Change is slow. That’s okay. Slower change is more likely to hold on and be sustainable.”