NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

In 2015, the Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative strategically held five screenings of the movie Paper Tigers—James Redford’s documentary about the dramatic reboot of a local alternative school after its principal became an advocate of trauma-informed care. Each screening was standing-room only.

They coupled the screenings with expert panel discussions addressing justice, health and education—the key sectors the network is targeting to address ACEs, build resiliency and impact system changes. To add further impact, the Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative held a VIP screening for foundation and policy leaders.

They also screened Paper Tigers for the general public at an evening show with an audience of faculty and students, community activists, psychologists, social workers and clergy. Two hundred people were added to their network after the public screening and vigorous, heartfelt panel discussion.

By the end of that week in November 2015, more than 500 people had seen Paper Tigers. Some wept. Others wondered whether the story of a small alternative school in the Pacific Northwest had any bearing on the large, resource-strapped, crisis-plagued Chicago public school system. A few foundation leaders said they wanted to change their funding priorities to focus more sharply on trauma and healing.

An Energized Network

The groundswell of interest sparked by the Paper Tigers screenings provided both “new opportunities and challenges” said Maggie Litgen, manager of the ACEs program for the Health & Medicine Policy Research Group, which helped found the Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative in 2011. “We’ve created this engaged audience…but what to do with the thousand people who want to be involved?”

For starters, the Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative now has all those names in its database; they’ll receive invitations to future trainings and events. “And I’ll be going to them for an environmental scan to find out: Are you doing trauma-informed work?” Litgen says. “The films helped us gauge which sectors are interested, and we’ve followed up with every funder who showed up.”

One success of the first year of the Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) project has been watching ACE awareness percolate upward in several large organizations and systems, said Alexandrea Murphy, senior manager at United Way of Metropolitan Chicago. “Several years ago, we had many individuals taking part who might not have been at the decision-making level in their organizations.”

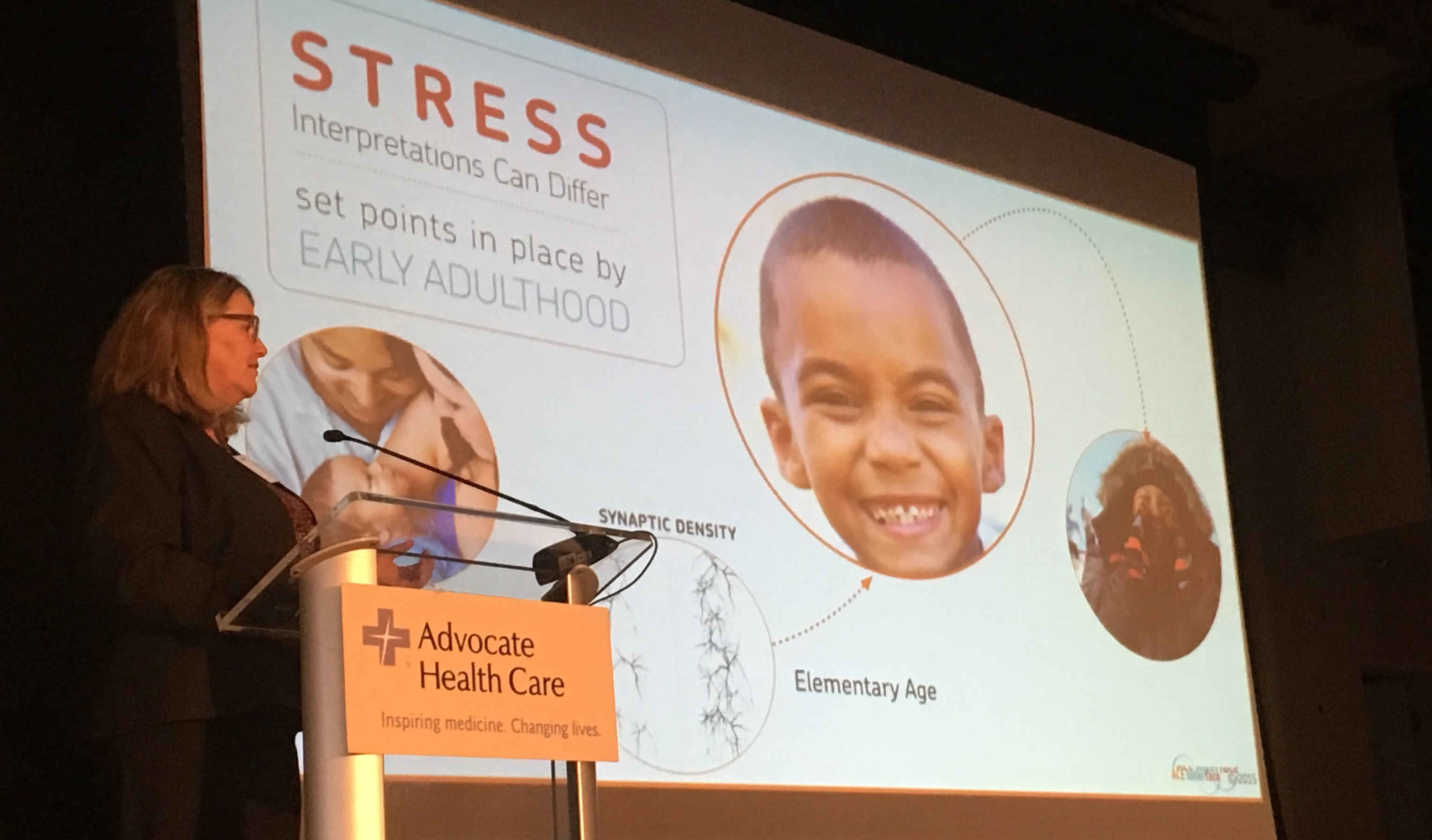

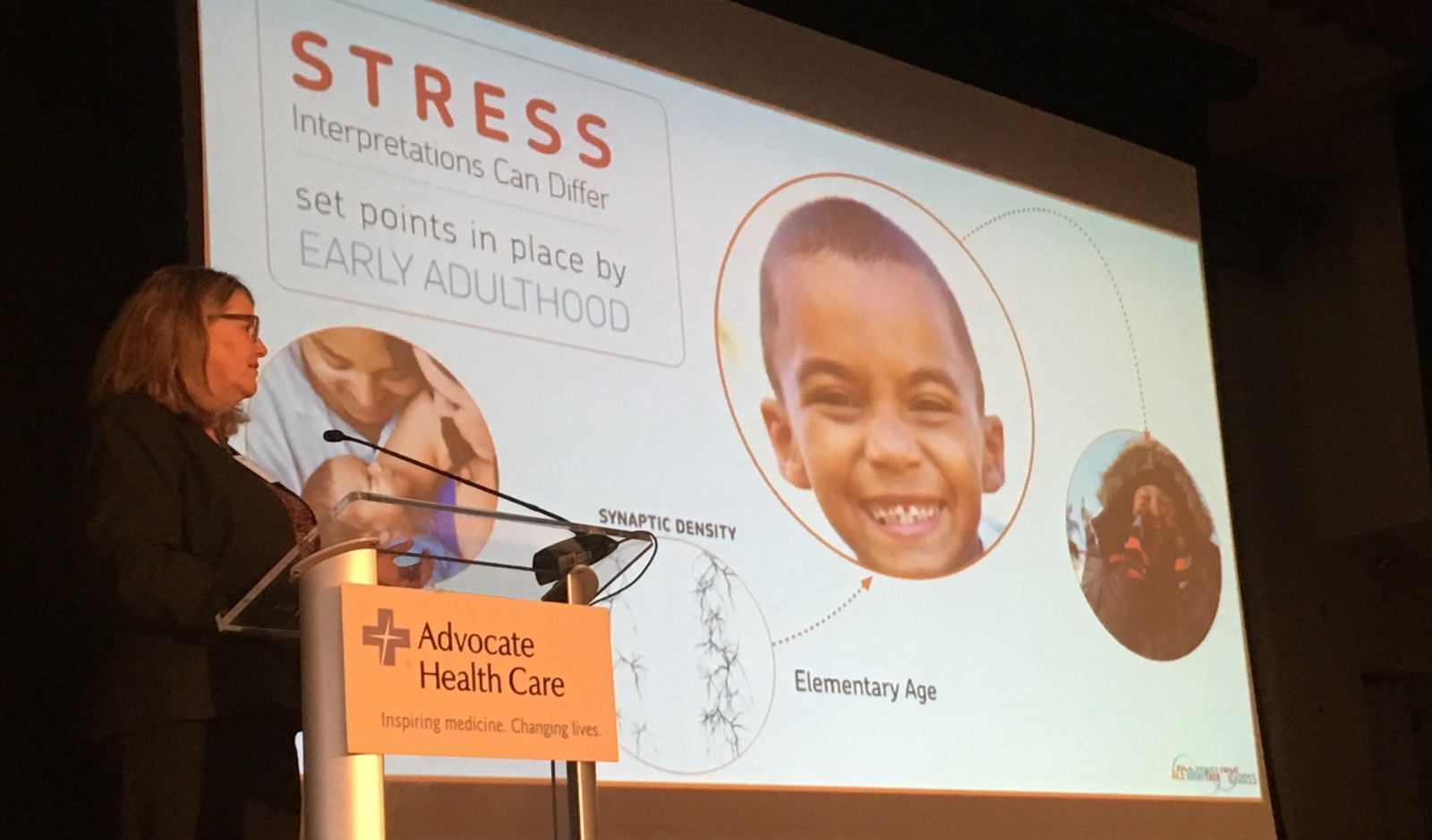

Now the Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative has more champions at the top, including United Way’s CEO and a vice president of Advocate Health Care—a faith-based, not-for-profit health system that is the state’s largest—who has sought help from the Collaborative to make the entire managed-care organization trauma-informed.

“The public health department has made a commitment to make the city trauma-informed,” said Litgen. “We’ve had our mayor sign off on a ‘Healthy Chicago 2.0’ plan that includes quite a bit of trauma language. We have leadership across silos in the city who are really committed to ACEs.”

Representatives of the faith community, as well as charter school networks, are among the network’s newly energized members. The Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative’s justice committee is working with the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, a state agency, helping to build the capacity of their victim services grantees as well as assist in developing strategies to evaluation trauma-informed practices.

New Challenges

Still, some sectors have proven difficult to reach. The Westat network analysis confirmed what Litgen and Murphy already knew: that the ACEs Response Collaborative was heavy on academics and health care/human services practitioners but light on folks from criminal justice and law enforcement.

Efforts to reach the police department with training on vicarious trauma in the near term have shifted to a long-term goal, recognizing the need to build relationships first during a turbulent time at the department is under scrutiny for racial bias. Additionally, ongoing struggles within the public school system—restructuring, budget crises and emergency meetings—have made it “hard to get people at the table to talk prevention when there are daily crises in our systems,” Litgen said.

In addition, philanthropic and grant-making organizations, while eager to make an impact on child adversity, may not understand the concept of a collaborative or the necessity for a long-arc view. “We want to teach funders that these are slow processes; you can’t flip a switch and change a culture. Thoughtful organizational change takes time,” she said.

A Message of Awareness

To further that goal, the Illinois ACEs Collaborative hopes to use the second year of the MARC grant to complete and share results of the environmental scan; so far, Litgen said, she’s received 339 responses and plans qualitative interviews with 20 of those programs. “We’re trying to glean: What does trauma-informed care mean and look like in an organization? We want to contribute to the research in a meaningful way, and to support agencies.”

The Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative will also work through United Way’s Neighborhood Network, partnering with existing community coalitions in four different neighborhoods on pilot projects aimed to bring the science of ACEs and resilience to the grass-roots level.

Illinois ACEs Response Collaborative members—a group of about 45 representatives from agencies including justice-based legal advocacy groups, top medical professionals, and the city’s Department of Public Health, as well as the state’s Department of Human Services and several universities—are carrying ACE awareness to the group’s target arenas of justice, education and health.

And data from the 2013 Illinois Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which for the first time included ACE questions, is helping to make the case that childhood adversity affects the physical and mental health, the behavior and employment prospects, of many Illinois’ citizens.

The survey showed that half of Illinois adults—almost five million people—reported at least one ACE; approximately one in six women and one in ten men said they’d experienced four or more. Of those who had four or more ACEs, 12% were unemployed, compared with 5.4% of those who had no ACEs.

From Awareness to Everyday Practice

Meanwhile, though funding and time, communication and accountability are ongoing challenges, Litgen is buoyed by hearing of ways that ACE awareness has shifted everyday practice—how, at Advocate Health Care, emergency department staff now take a trauma-informed approach to debriefing after a child dies, or how an alternative school teacher, after learning that some students spent 60% of their time thinking about past trauma, now plans to begin the day with breathing exercises or meditation to help her class focus.

“We are working towards major system changes and are collecting small, though significant, wins along the way,” Litgen said.

This article is part of a community update series following the ATR networks participating in the MARC 1.0 Initiative. Read the other updates from Illinois: