NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

In Toole County, Montana, deputy sheriffs call a school counselor, from their patrol cars, after responding to a traumatic incident—a domestic abuse call, an overdose, an arrest—that involves a child.

“Handle with care,” they tell the counselor, and they give the child’s name. The counselor passes that information to teachers: a quiet heads-up that the student might be hungry or sleepy, tearful, angry or distracted by whatever happened at home.

“My teachers love it,” says Mary Miller, chair of the Toole County Affiliate of Elevate Montana, a multi-sector network that aims to boost the well-being of children statewide through ACEs awareness and resilience-building.

“[Handle with Care] clues them in that the child…suffered trauma the night before. It’s worked extremely well.”

Miller says her community—3500 people scattered near the state’s border with Canada—would never have known about Handle with Care, a program launched in 2013 in West Virginia, if not for Elevate Montana.

Tina Eblen directs ChildWise, Elevate Montana’s backbone agency. She says it’s because of robust local affiliates—and passionate leaders like Miller—that Handle with Care has spread to other parts of the state: to Kalispell and Libby and Shelby. There’s sufficient momentum, she says, to introduce an amendment to a Safe Schools bill in Montana’s next legislative session, with language endorsing the use of Handle with Care statewide.

It’s a clear example of how local affiliates, now numbering fifteen across the large and sparsely populated state, both contribute to and benefit from Elevate Montana’s push for broad ACEs awareness, trauma-informed care and system-wide change.

Eblen doesn’t recruit new communities to join Elevate Montana; typically, local leaders will learn about the movement and call her, often when their community is visibly struggling with a rash of suicides, opioid overdoses or violence.

“People start to take notice and say: We’ve got to stop this,” she says. “It’s all word-of-mouth, people saying, ‘What can we do to change our community?’ I’ll set up a meeting and talk about what they’re looking for and what we can help with.”

Eblen listens for signs of readiness: to thrive as an affiliate, a community needs at least one impassioned leader and a range of stakeholders at the table. “It can’t just be the school district. It can’t just be a church,” she says. “You have to have buy-in from all the sectors in the community.”

Elevate Montana can’t offer funding to local affiliates; what Eblen can provide is guidance, resources and training—broad introductory ACE presentations open to anyone, and more targeted sessions on the Handle with Care program, coalition-building and trauma-responsive workplaces. Recently, in response to one affiliate’s request, Elevate Montana created a new presentation focusing on resilience at the individual, family and community level.

“We go and train local presenters within the community. We like that model because people listen to people they trust,” Eblen says. “One of the foundations of the Elevate Montana affiliate program is getting at least 50 percent of your community to understand the impact of toxic stress and trauma on the developing brain.”

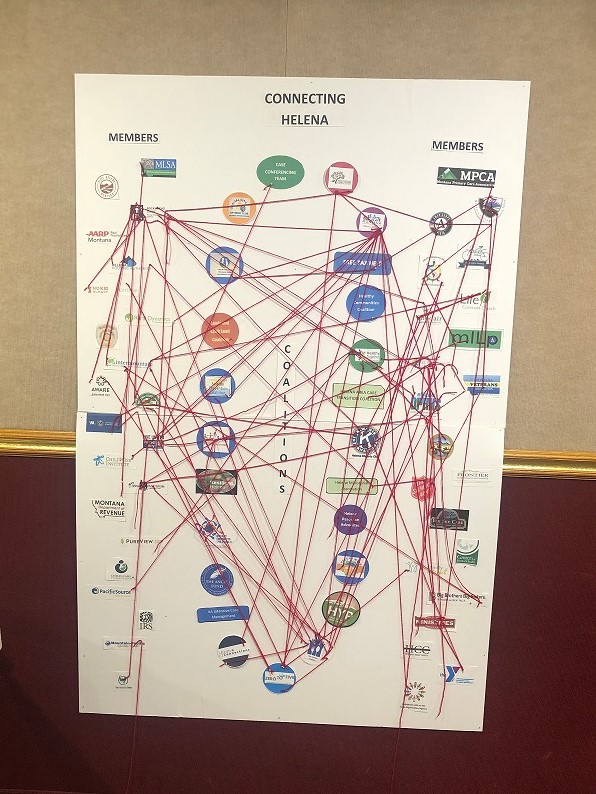

In 2015, when Rebecca Hargis, a retired family and child therapist, formed the Helena Affiliate of Elevate Montana along with colleagues from juvenile probation, the school system and child welfare, widespread community awareness was at the top of her agenda.

In 2015, when Rebecca Hargis, a retired family and child therapist, formed the Helena Affiliate of Elevate Montana along with colleagues from juvenile probation, the school system and child welfare, widespread community awareness was at the top of her agenda.

“We started having free ACE trainings at the library and at one of our local churches,” she says. The group showed Paper Tigers at the middle school, to an audience of 500, and had ten community members trained to be ACE presenters.

Local child welfare workers joined the affiliate. So did the owner of several McDonald’s franchises, who wanted to bring trauma-awareness to her managers. A staff member at Big Brothers Big Sisters of Helena and Great Falls wants to make ACE training mandatory for all the “bigs” before they’re allowed to meet the “littles” at their homes.

In collaboration with the local Zero to Five initiative, which has ACE awareness as one of its goals, Hargis is working on a plan to provide ACEs-and-resilience training to the staff of a local bank as well as other businesses. And the 2019-2022 Lewis & Clark County Community Health Improvement Plan includes “trauma-informed practices and ACEs” as one of three priorities to improve children’s health.

“We want to educate, so that we truly can have a community that is resilience-based,” she says. “All the people who care about this give me hope that someday—maybe not in my lifetime—we will significantly reduce adverse childhood experiences.”

In tiny Toole County, Miller says, most police officers have received trauma training, as have school counselors, Head Start workers and county extension agents. She’d like to see correctional officers and newly hired teachers also receive training about ACEs, toxic stress and resilience.

“My community is learning a lot about brain development and how trauma affects the brain,” Miller says. “We really want to work on the resilience part and teach kids coping skills, ways to address things when they are triggered.”

She tries to present information about ACEs and resilience wherever she can: at fairs, at camps for at-risk kids and through casual chats in an area where word-of-mouth remains a persuasive form of education.

Eblen says ACE-awareness has caught on more swiftly in rural areas. “It’s a much tighter network of people,” she explains. “People talk much more efficiently and quickly because everybody knows everybody.”

She’d love to organize a gathering of all fifteen Elevate Montana affiliates—the last one was in fall 2018—and to travel more frequently among them, but funding (and now, COVID-19) remains an obstacle to that kind of in-person relationship-building.

For now, Eblen notes the impact of Elevate Montana in large and smaller ways—the growth of Handle with Care, for example, and the story she heard of a supervisor at a Helena McDonald’s who was faced with a screaming customer, irate because the food she’d ordered from an app wasn’t ready when she arrived.

The supervisor apologized and gave the woman free food; the next day, she called with her own apology and an explanation for her outburst: she’d been on the way to pick out a headstone for her child.

"The supervisor said, ‘I had no idea what was happening to her. I was just listening.’ I thought: She will never forget that experience, and he will never forget that experience,” Eblen says.

Across the state, the work continues: In Toole County, Miller envisions a huge community event, a health fair with booths and stations to engage residents in more learning and discussion about ACEs, brain development and behavior. In Helena, Hargis likes to borrow a phrase from climate-change activists: transformative resilience. “That means we’re not going to just bounce back. We’re going to be bigger, better and stronger. We’re going to transform our crises into something positive.”

Anndee Hochman is a journalist and author whose work appears regularly in The Philadelphia Inquirer, Broad Street Review and in other print and online venues. She teaches poetry and creative non-fiction in schools, senior centers, detention facilities and at writers' conferences.