NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

A jigsaw puzzle, no two segments alike, that comes together to form a bright picture only when the whole community helps to assemble it.

The Buddhist image of “Indra’s Net,” a web in which a jewel at each juncture reflects all the other jewels (and is reflected in them), demonstrating the infinite connectedness of the universe.

The branching patterns found in human capillaries, cedar fronds, and a head of Italian broccoli.

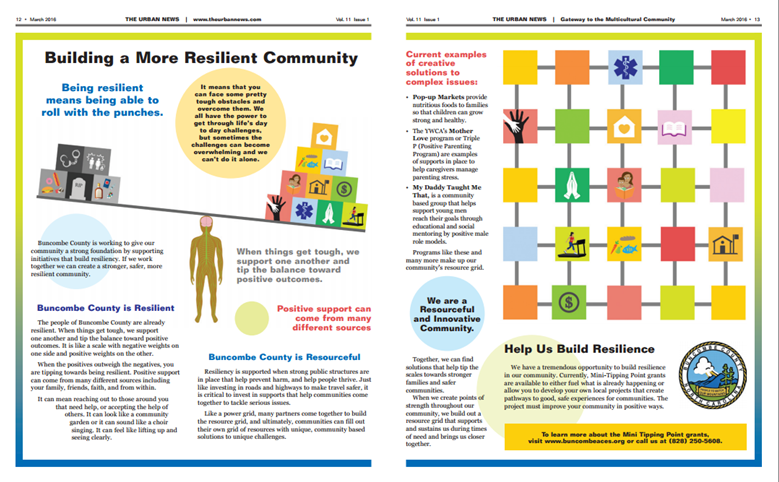

When wrestling with ideas like adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), trauma, health and community—and how they relate to each other, metaphors like these help carry abstract concepts down to earth and make them accessible to a range of audiences. So when the Buncombe County ACE & Resiliency Collaborative in North Carolina wanted to explain community resilience and inspire people to make it happen, they partnered with the FrameWorks Institute of Washington, D.C., to find just the right “sticky” metaphors and images.

“Every great movement has a compelling narrative,” says Lisa Eby, human resources director of Buncombe County Health and Human Services and a member of the ACE & Resiliency Collaborative. She noted that the push for same-sex marriage legislation gained momentum when the message shifted from “marriage equality” to “It’s about love.”

FrameWorks has taught the group from Buncombe County the science involved in creating effective messages: How our brains make sense of the world by unconsciously snapping new information into existing frames. When thinking about adversity and health, many people carry frames that suggest individual responsibility and fatalism—concepts such as “pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps” or “nothing can be done.”

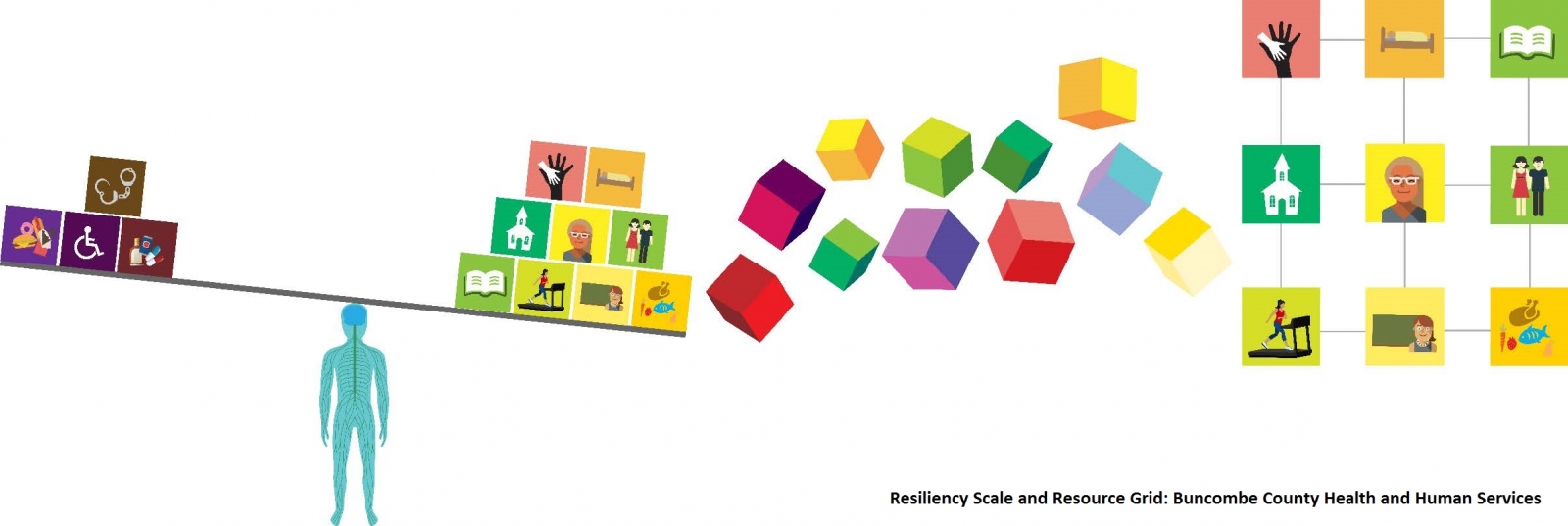

FrameWorks’ research has found two metaphors that work to counter these ideas and drive home the story of resilience. One is the “resiliency scale,” a balancing rod loaded, on one side, with an individual’s positive and protective factors—for instance, “My grandmother…I’m a fast runner…I go to summer camp.” On the other side are negative factors that could undermine resilience—“My dad is in jail…I have asthma…I have nowhere to play.”

The Buncombe County group has used the resiliency scale in trainings, inviting participants to list their own positive and negative factors on sticky notes and then to note how adding positive elements—a spiritual practice, coping skills, a jail visiting program—can tip the scale toward resilience even when things go wrong. The next step, Eby said, is to look at those positive factors as part of a community-based “resource grid,” noticing the gaps and working together to fill them—for example, with more outdoor play spaces, cultural heritage events, or after-school programs.

“The idea is that we need to use common sense and know-how to solve community problems so we all can thrive,” she says. To this end, Buncombe County created “Positive Tipping Point” mini-grants for community projects that could help shift the scale toward resilience. They have already received 50+ applications for efforts including neighborhood clean-ups, community gardens, and cultural projects.

At a gathering of MARC leaders in November 2015, Sandra Bloom, an associate professor at Drexel University’s School of Public Health and founder of The Sanctuary Model, offered an array of other metaphors to explain interdependence, system change, and community violence—including the image of a human immune system (see Resources below).

The immune system guards itself with sentinels whose job is to sense “invaders.” A breakdown in immunity can lead to infection, disease or chronic inflammation. Violence, she said, operates the same way. “As infection is an exception to the rule of health, violence is an exception to the rule of peace.” And when it erupts—whether in the form of domestic abuse, organizational breakdown, or community conflict—we must ask what happened to the social immune system.

Metaphors matter. A “war on cancer” conjures images of battle and victors, while describing a neighborhood as an “ecosystem” evokes balance and interdependence. The Community Resilience Initiative in Washington used the metaphor of bridge-playing to inspire the slogan “Resilience Trumps ACEs.” The Alberta Family Wellness Initiative created a video of “brain-building” that shows members of the community devoting skills and time to that essential project, much the same way neighbors would lend hands to raise a barn.

Metaphors help determine whether listeners think of ACEs as destiny or opportunity, whether they see themselves as broken wheels or works-in-progress—and whether they feel deflated by grim statistics or inspired to join others on the path toward resilience.

See the resiliency scale and resource grid metaphors in action in this tear sheet from Buncombe County in The Urban News (March 2016).

Click on the image for a PDF

See how Dr. Sandra Bloom uses an immune system metaphor to illustrate how a community can defend itself against violence and promote peace in this slideshow excerpt from her keynote address at the MARC 2015 Convening.

Click on the image for a PDF

Anndee Hochman is a journalist and author whose work appears regularly in The Philadelphia Inquirer, on the website for public radio station WHYY and in other print and online venues. She teaches poetry and creative non-fiction in schools, senior centers, detention facilities and at writers' conferences.