NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

Todd Garrison’s background was in venture capital, sales and marketing. So when he heard a presentation in 2008 by Rob Anda, co-investigator of the original ACE Study, the facts and figures caught his notice.

“It wasn’t personal for me, though I have three ACEs myself,” said Garrison, now Executive Director of the ChildWise Institute, a four-year-old non-profit that focuses on child well-being. “The brain science is undeniable. That was the ‘aha’ moment for me.”

Since then, he has watched others across the state—teachers and nurses, mental health counselors and school bus drivers—wake up to the understanding of childhood adversity and its lifelong impact.

In 2013, ChildWise created Elevate Montana, an ACE-informed statewide initiative to boost the well-being and future of Montana’s children. Numbers pointed out the urgency and need: the state ranks 47th in child health, according to KidsCount, a national agency that tracks child well-being in the U.S. In 2013, Montana had one of the highest teenage suicide rates in the nation.

When the state’s Department of Health & Human Services included ACE survey questions in the BRFSS in 2011, the results were equally grim: 60% of Montana adults had an ACE score of at least one, with 17% reporting four or more ACEs.

Garrison believes there is good news in those numbers: They mean that everyone can identify with ACEs. “Even if you have an ACE score of zero, you know somebody who doesn’t have a score of zero. ACEs are not ‘those people.’ ACEs are us.”

Elevate Montana has worked to spread that message. A 2013 ACE Summit in the western part of the state brought together more than 225 people, including mental health and social service professionals, teachers, school superintendents, law enforcement staff, nurses, judges, legislators, adoptive and biological parents.

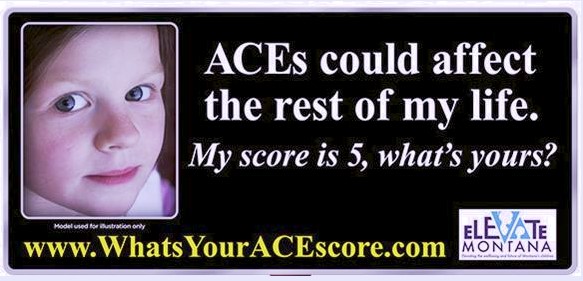

A second summit in eastern Montana the following year drew 240 people. For 30 days prior to the gathering, Elevate Montana placed 11 billboards in various cities to fan curiosity about ACEs—a close-up photo of a wide-eyed child, with the words, “ACEs could affect the rest of my life. My ACE score is 5, what’s yours?” At the bottom of the billboard was a web address (WhatsYourACEScore.com) where people could tally their own ACEs. To date, 1,000 people have done so.

The initiative also created wallet-sized cards with a message similar to the billboards and facts about ACEs. “It gives somebody a tool to start conversation,” Garrison said.

The most recent ACE Summit, in October 2015, was titled “Adversity is Not Destiny: Overcoming ACEs through Actions” and drew 400 people; the event was sold out a month in advance.

Between the summits, Elevate Montana has worked through other channels to share knowledge about early adversity. Learning seminars called “Why They Do What They Do” have trained parents, teachers, probation officers and parents in early brain growth and child development. Twenty-one ACE Master Trainers visit a range of groups and the Montana Department of Health & Human Services has committed to bring ACE training to all 3,000 of its staff. The Elevate Montana network includes foundations, non-profit agencies, hospitals, Blue Cross Blue Shield and the Montana Supreme Court.

In September 2015, Elevate Montana conducted its first all-staff training in a school district, reaching teachers, counselors, administrators, kitchen staff, custodians and bus drivers. Paper Tigers, James Redford’s documentary about the trauma-informed reboot of an alternative school in Washington, screened twice in Helena in conjunction with the most recent summit.

Garrison said he’s proud of the energy and buzz around ACEs across the state: the baseball caps emblazoned “Elevate Montana,” the stacked-up requests for trainings, the phone calls from people who want to volunteer. Now, he said, many are asking about the next step.

“You present ACEs, and people say, ‘Well, what do I do next?’ What do you bring in to help them develop trauma-informed and resilience-building strategies?” That’s what he hopes Elevate Montana can learn from MARC partners. “I want to learn from the best of the best how to accelerate our work and make it more meaningful.”

Specifically, he’d love to hear from communities that have been successful in galvanizing physicians and others in health care, a sector that’s proven especially hard to engage in Montana. He’s curious about whether others have collected data on interventions involving parents whose children are in custody—that is, whether those high-ACE-score adults, once exposed to knowledge about ACEs, are motivated to make changes in their lives.

Garrison has seen such transformation first-hand, in the life of a young woman who volunteered at ChildWise. “She had liver disease, smoking and drinking problems. Her life has dramatically changed because of getting involved with ACEs work.” She quit smoking and is now pursuing a master’s degree in psychology.

“We’re seeding what we hope will be a movement across Montana,” Garrison said. “Apple is so good at creating a culture of wanting to belong. I’d love for us to be the iPod of mental health.”

This article is part of a community update series following the ATR networks participating in the MARC 1.0 Initiative. Read the other updates from Montana: