NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

“What are your signs of stress?” asked the leaders of a recent mindfulness webinar hosted by the Philadelphia ACE Task Force (PATF), held during the week that U.S. cases of COVID-19 neared half a million and more than sixty Philadelphians had died of the disease.

Participants spilled their responses into the chat box: “headache…teeth grinding…can’t think clearly…nervous stomach…ruminating thoughts…muscle pain…itchiness…bad dreams.”

Then co-leader Meghan Johnson, project manager with the Support Center for Child Advocates and a longtime trainer on vicarious trauma, led the group through an exercise designed to counteract those anxious sensations. “Breathe in like you’re smelling a flower,” she instructed. “Breathe out like you’re blowing out a candle.”

Then co-leader Meghan Johnson, project manager with the Support Center for Child Advocates and a longtime trainer on vicarious trauma, led the group through an exercise designed to counteract those anxious sensations. “Breathe in like you’re smelling a flower,” she instructed. “Breathe out like you’re blowing out a candle.”

The webinar, “Mindfulness in the Time of COVID-19” was one piece of the PATF’s response to the stress, fear and trauma rippling through the city amidst the coronavirus pandemic. The session grew from the PATF policy work group’s ongoing project of addressing and preventing secondary traumatic stress among city workers, including police, health care providers, unionized employees and first responders.

As the world shudders through an unprecedented crisis, networks like the PATF are stepping up to gather and share information, create opportunities for virtual connection, remind people about the science of toxic stress and build on community efforts to foster resilience in the wake of trauma and uncertainty.

“This really is an opportunity,” says Melissa McGinn, co-coordinator of the Greater Richmond Trauma Informed Community Network (GRTICN), one of 26 such coalitions throughout Virginia. “This is why we have these networks, for times like this. We’re all in this, and we need to use each other right now to mobilize our resources.”

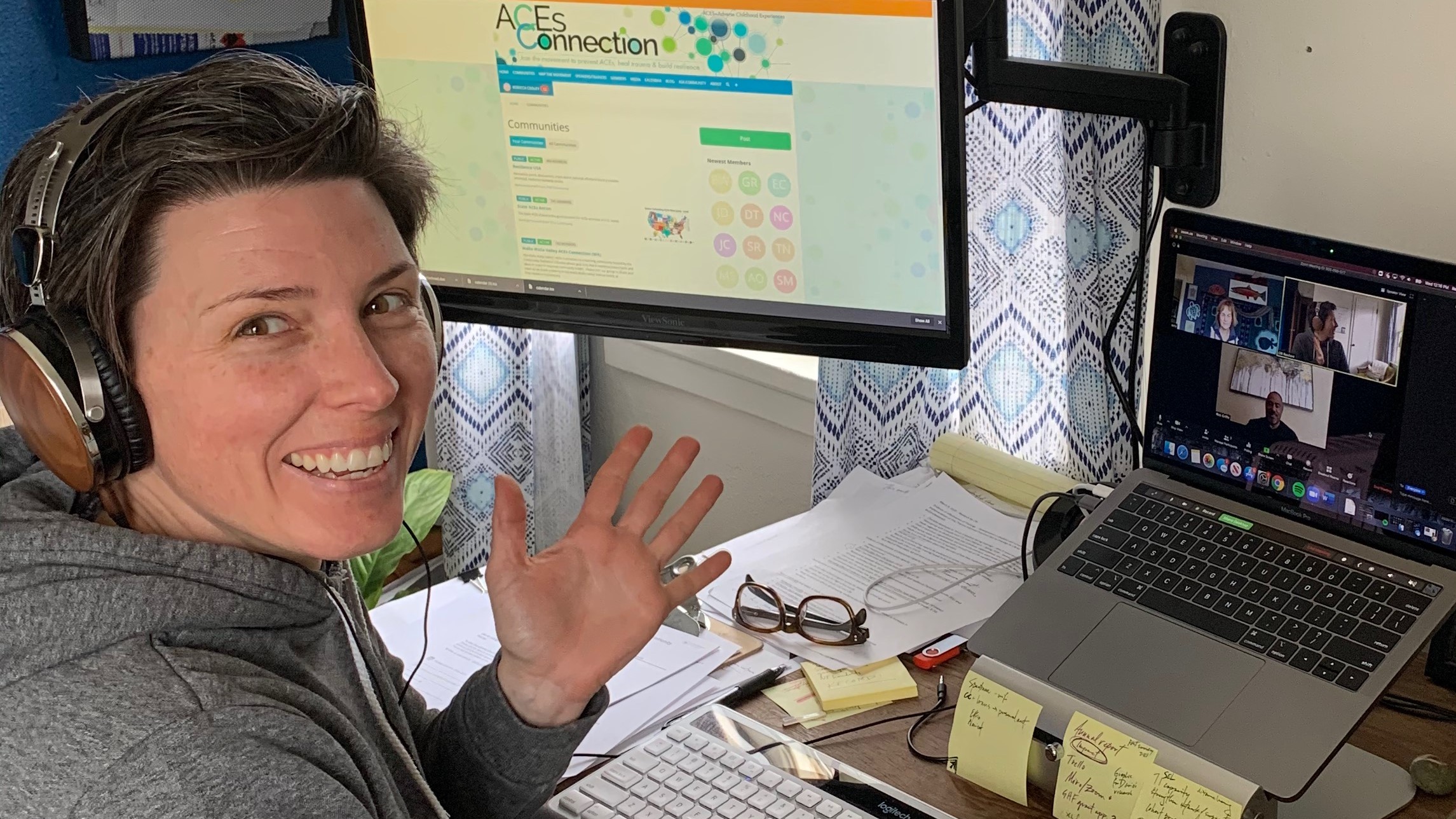

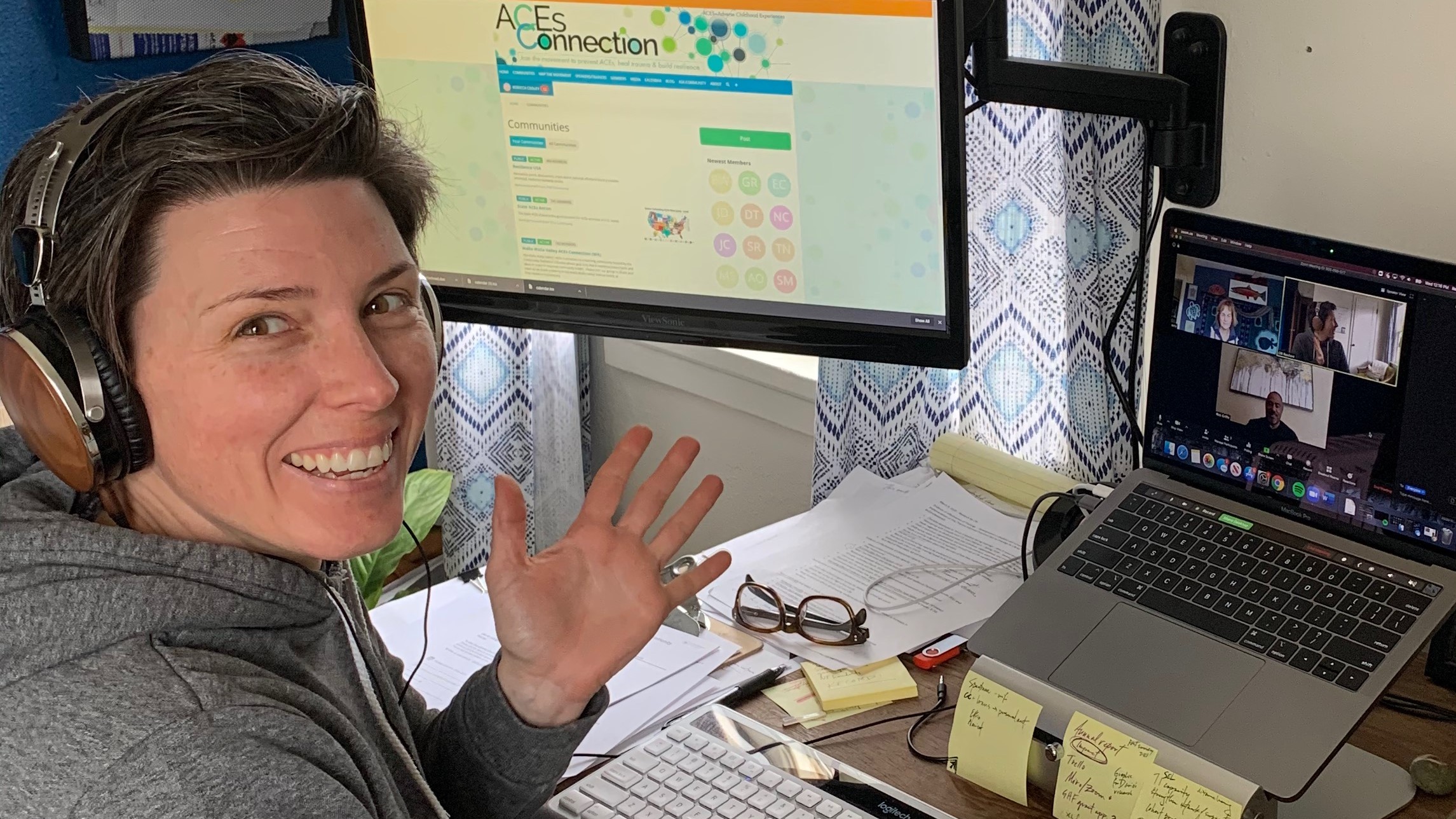

For McGinn’s network, that mobilization began in mid-March, when Virginia’s schools closed and the reality of COVID-19 set in. The GRTICN had a regular meeting scheduled, and leaders decided to hold it, on Zoom—but instead of the usual agenda, they planned a 30-minute session of guided meditation, chair yoga and stretching. “It was an opportunity for people to connect and be present,” McGinn says. Sixty people tuned in.

Shortly after that, McGinn—who also serves as state coordinator for Virginia’s TICNs—began sending weekly e-newsletters (see right column of this page) to all of the state’s networks, including mental health access lines, links to sites for food distribution and free Internet, and resources for talking with kids about COVID-19. They are hosting a virtual meeting of community members, and another with representatives from the police department, health care system and the school district.

“We’re trying to be the convener of these forums…not to figure out what people need, but to create a space for people to have a voice, to listen and get that information out,” McGinn says.

Across the country, other networks are rising to meet the current crisis with innovations that could easily be replicated in other localities:

In the past, cross-sector networks focused on ACEs, trauma and resilience have mobilized to address climate-related disasters such as wildfires in California and hurricanes in Florida. This crisis calls for some of the same tools: preparation, collaboration, a track record of fostering trauma-awareness across the community. In other ways, this pandemic is unique.

“It’s a shared experience across the world,” says McGinn of the Richmond network. “At the same time, there is so much unknown. There’s no protocol for this.” She and others note the ways COVID-19 underscores the devastating inequities in our society, with low-wage workers, people of color, the elderly, the undocumented and those with disabilities feeling the hardest impact.

Another unique challenge of this crisis is the call for physical distancing and sheltering in place. That’s why the Community Resilience Initiative (CRI) in Walla Walla, Washington has been emphasizing “kindness and connection” in the network’s blogposts; one discussed “distance connecting,” suggesting that families use Skype, postcards and phone calls to counter their isolation.

The CRI launched a weekly series of trauma-informed community meetings, chances for people to share resilience strategies and build on years of trauma-informed work across sectors in the area. “We’re trying to maintain and build relationships,” says Rebecca Cooley, associate director of the CRI. “To remind people that there are protective factors and strategies that are extremely important during this time.”

The CRI launched a weekly series of trauma-informed community meetings, chances for people to share resilience strategies and build on years of trauma-informed work across sectors in the area. “We’re trying to maintain and build relationships,” says Rebecca Cooley, associate director of the CRI. “To remind people that there are protective factors and strategies that are extremely important during this time.”

In an article published by the International Transformational Resilience Coalition (ITRC), social systems and climate change expert Bob Doppelt wrote about the crucial role of cross-sector networks in responding to the massive disruptions of the coronavirus pandemic.

He advocates “innovative community-based interventions” that include teaching mindfulness and other wellness strategies, identifying gaps in support services and providing resilience skill-training for first responders and local leaders (get the full recommendations from ITRC here).

While there is no precedent for a pandemic, networks’ years-long efforts to address ACEs and build resilience can provide a framework, and a language, for responding to COVID-19 and its enduring impact.

“Work in the ACEs and trauma world has concepts that are very helpful for people now,” says Carolyn Smith-Brown, a member of the PATF work group that hosted the recent mindfulness webinar. “The brain science around this is reassuring. We can say, stress is a normal response, and there are tools we can use to help manage that stress.”

Additional Examples of Supporting and Strengthening Pandemic Response Efforts from ACEs, Trauma, and Resilience Networks: