NATIONAL ATR NETWORK SURVEY

Hundreds of ACEs, trauma, & resilience networks across the country responded to our survey. See what they shared about network characteristics, goals, and technical assistance needs.

Teri Barila, director of the Community Resilience Initiative (CRI), figured few people would venture to Walla Walla to learn about brain science, self-regulation and resilience.

She was wrong. A June 2016 conference, “Beyond Paper Tigers,” drew 250 people—some from as far away as Texas, New Mexico and Tennessee—to sessions on “Why Brain Science Matters,” “The Trouble with Triggers” and “Inside Out: Learning About Emotions.”

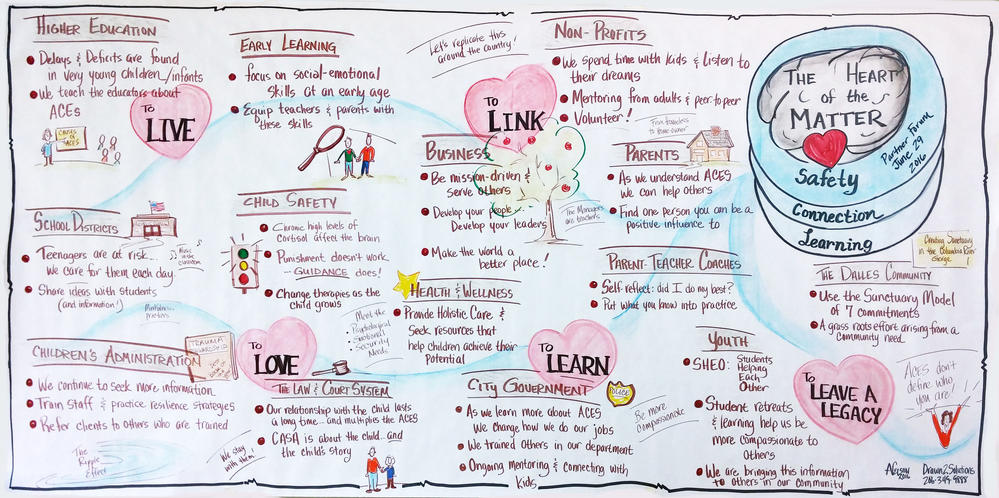

In a two-hour partner showcase, representatives of 14 different agencies and organizations answered the question that threaded through the entire two-day event: “What is The Heart of the Matter?”

The one thing Barila regretted was that she hadn’t scheduled a break-out session on how the whole thing came to be.

Barila can’t talk about the first year of the Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC) grant—a project that pairs Walla Walla’s CRI with the Whatcom Family and Community Network (WFCN)—without discussing the scaffolding built long before ACEs became a buzzword.

Starting in the early 1990s, Washington established a statewide Family Policy Council that worked with 42 local affiliate, grass-roots collaboratives that aimed to design and implement community responses to problems such as teen pregnancy, youth substance abuse and domestic violence. The Family Policy Council worked on the premise that all people have strengths, that leadership should be local and that the most enduring solutions are citizen-driven.

“We scaffolded the Community Resilience Initiative and the MARC grant on that history of learning and community of practice,” Barila says. “You can’t take that out of the equation.”

For Barila and Kristi Slette, executive director of WFCN, the MARC project has provided more ways to further that learning, share it with members of both communities and spread it throughout the state.

A Chance to Reexamine and Improve

A week before CRI’s successful “Beyond Paper Tigers” conference, WFCN held its own event, a “Community Conversation on Resilience and Equity” that drew 100 people to break-out sessions on topics including “Resilience: Bouncing Forward,” cultural humility and self-care. Two months later, 25 of those participants gathered to talk about how they could train together and share their research.

For the Washington MARC network, every conversation—even those that falter—is a chance to reexamine and improve. “We learn most from our crashes,” Barila says. For instance, Slette realized at the WFCN summit that different communities understand “resilience” differently; some even recoil from that word.

“Within local Native American communities, the word ‘resilience’ may not always be perceived as positive,” she says. “In our rural communities, resilience doesn’t mean the same thing as it does in downtown Bellingham. The summit was an opportunity to hold and contain all the different words and concepts that mean resilience—equitable, strong, gifted, gritty, compassionate.”

Barila, meantime, has become more sensitive to unintended triggers that may reawaken someone’s trauma. After one meeting a participant—a woman without professional credentials whose label was simply “champion of resilience”—said she felt intimidated when people introduced themselves with their job titles. Barila suggested opening future meetings with the question, “What brings you to this particular table today?”

Language and Assumptions

She and other CRI leaders continue to examine the language and assumptions with which they talk about ACEs and resilience. When a marketing expert suggested using ACE data—stark numbers about the increased risk of negative health and behavior outcomes—on yard signs, the CRI team rejected that idea, opting instead to emphasize the power of hope and compassion.

“Hearts trump ACEs Every Time” declares the banner on CRI’s website. Flags hung downtown for the fourth annual Resilience Awareness Month in October echoed that message. An ongoing question is “How do you present this in a way that doesn’t blame, shame, trigger or punish, but allows you to move forward?” Barila says.

Community Connections

Both networks have long been focused on community connection, leadership, communication and on deepening school practice even before the galvanizing success of “Paper Tigers.” James Redford’s documentary is about a Walla Walla alternative high school that saw huge changes after the CRI’s community initiative helped Lincoln High school become trauma-informed.

This year, CRI is bringing resilience-building strategies to three elementary schools and the local Head Start program. Strategies include catchy tunes that help kids learn how their brains work, encouraging mantras to hang in staff rooms and “safe zones” with stuffed animals and beanbag chairs for kids who need a quiet corner.

The network has also met with the CEO of Walla Walla’s largest clinic to discuss a pilot project in which a “navigator” would connect parents to resources, including home visits and other early interventions that have been shown to reduce ACEs and build resilience.

In WFCN, Slette sees growing interest in rural areas. Network partners have begun work in the Columbia Valley community, in the Mount Baker School District and in the Nooksack School District. A diverse mix of participants include school district staff, faith-based representatives, law enforcement, social services and community members who live in and serve these more isolated communities. They have met to identify the unique strengths, assets and characteristics that build resilience in the lives of children and families as they work to develop frameworks for resilience that fit who they are culturally.

Hope and Strength

Barila remains curious about the steps that lead to a paradigm shift for individuals and for systems—why one person decides to make a change after learning about ACEs and brain science while others are unfazed. “Our next level of research, a survey we’ll be giving to every organization that’s been involved with us, is to ask why or how they’ve been able to make that shift,” she says.

All of that work—every summit, every meeting, every banner stretched across Main Street—is pointed toward the long-distance prize of policy change. One recent development suggested that effort was working: A commission formed to fix Washington’s services to children and families proposed creating a new Department of Children, Youth and Families that would combine youth services with early learning and parts of the juvenile justice system. According to the proposal, the new department would draw on the science of ACEs and neurodevelopment, emphasizing prevention and integrated, easy-to-navigate services.

Barila tries to remember—and remind newer leaders—that such huge shifts take time. “We spent almost a year doing one-on-one private meetings with almost all the agencies in town as we were scoping out the CRI,” she says. “This is a journey. You have to take the time to nurture this work.”

“Face-to-face, real-life, human communication is central and core,” Slette adds. “There is so much fear already. This movement will benefit from moving hope and strength to the forefront of our message.”

This article is part of a community update series following the ATR networks participating in the MARC 1.0 Initiative. Read the other updates from Washington, including Walla Walla and Whatcom Counties: